Push the Limit: Training for Energy Intake

5min reading

Push the Limit: Training for Energy Intake

For many endurance athletes, the start of the competition season is an exciting time. While some are already racing, others participate in virtual events or go for strava KOM. Regardless of the approach, this is the perfect opportunity to optimize energy absorption and refine energy strategies. Just as training intensifies with rigorous intervals, anaerobic exercises, and race-paced workouts in preparation for upcoming competitions, athletes can also "train the stomach" to handle increased energy intake effectively.Why Train for Energy Intake?

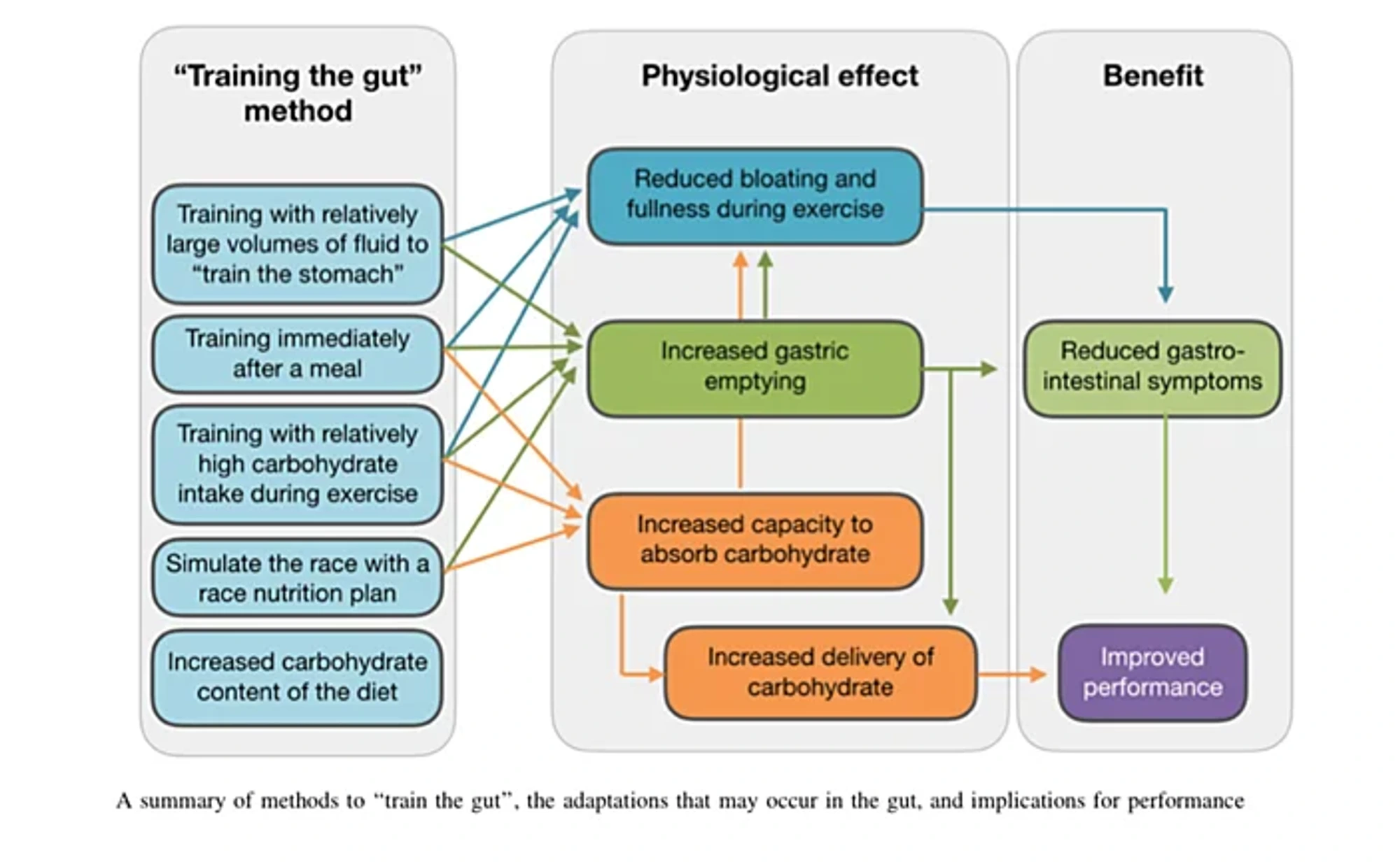

The principle of specificity is a well-known concept in sports science, meaning "you become good at what you practice." This principle also applies to energy absorption. The body gets proficient based on its exposure: consume a diet rich in fats, and it becomes adept at using fat as fuel; increase carbohydrate intake, and the body enhances its ability to process them. Why endurance athletes should focus on carbohydrates is a topic for another discussion, but in brief, the body burns carbohydrates more efficiently, requiring 5-7% less oxygen compared to burning fatty acids.

This 5-7% might seem insignificant, but it equates to about 10 additional heartbeats per minute to maintain the same pace. We all know how challenging an extra 10 beats per minute can feel! As glycogen stores are depleted, more oxygen is needed to extract energy from fat, leading to an increased heart rate, pushing you beyond your threshold, and causing you to "hit the wall."

Alternatively, you might have to slow down to maintain the correct heart rate, which can also be considered hitting a wall – a sudden drop in intensity or speed. This incremental increase in heart rate as glycogen stores are used up is extremely inefficient, especially during a race, when adjusting your system to handle more energy isn't that complicated.

In essence, preparations aim to teach the body to rely more on the oxygen-efficient carbohydrates. Consuming more carbohydrates during activities conserves stored muscle glycogen, delaying that dreaded wall. Practicing energy intake is also crucial from a technical and tactical perspective. Being able to seamlessly drink or use gels is vital to sticking to an energy plan.

What About My Fat Adaptation?

During exercise, carbohydrate uptake by muscles is largely independent of insulin. This means insulin secretion is almost nullified as the muscles immediately absorb and burn the carbohydrates. This phenomenon is one reason you still achieve fat adaptation even when consuming sports drinks. Normally, insulin inhibits fat oxidation and increases carbohydrate burning. However, since carbohydrates are metabolized without insulin during exercise, a significant portion of fat adaptation (70-80%) still occurs. Clever, right?

How Should You Approach This?

It takes about 4 weeks to nutritionally adapt for a competition. Therefore, the basic rule is to train more competition-specifically (both physically and nutritionally) at least a month before the race begins. Nothing in our body changes overnight. Hormones, transport proteins, and enzymes, all vital to our metabolism, are gradually regulated based on diet and exercise routines. Studies have shown it takes about 4 weeks for the body to enhance carbohydrate uptake. If carbohydrate intake has been low for a while, suddenly switching to a higher, competition-specific intake can lead to common digestive issues. This regulatory decrease in carbohydrate metabolism becomes evident when athletes who've avoided carbohydrates for three days are given sports drinks. These athletes developed a mild glucose intolerance, making their muscles less efficient at absorbing carbohydrates. Moreover, it seems muscles prefer to store the carbohydrates rather than use them for immediate energy.

A 2010 study adopted a simple setup, dividing athletes into two groups. Both groups cycled for 100 minutes on a test bike. One group drank a 10% carbohydrate sports drink solution, resulting in 60g of carbohydrates consumed during the 100-minute cycling session. Additionally, this group was given an extra 1.5g of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight for each training hour over the 4-week period. The other group trained as much but only drank water during their sessions.

Despite all participants consuming the same total daily energy, just these minor adjustments (extra dietary carbohydrates and sports drinks during workouts) led to a 16% improvement in carbohydrate absorption and utilization among the carbohydrate-consuming athletes. Their oxidation rates increased from 55g/hour to 65g/hour (pure glucose). This might sound trivial, but an extra 10g per hour during a long race adds up to significant oxygen savings.

Practical Tips:

- Increase carbohydrate intake in 1-3 sessions per week leading up to the competition season.

- Boost intake during endurance sessions and try the planned energy strategy during speed sessions.

- Combine the increased energy intake with race-specific sessions.

- Push your boundaries. If you usually manage 80g of carbohydrates per hour during a race, aim for 100g/h during training.

Summary

Your body excels at what it is exposed to. If you train in a specific way and adopt a certain lifestyle, your body will adapt accordingly. If you're among those who experience discomfort from hydration and/or energy intake, our recommendation is to specifically train to overcome this weakness. By doing so, your stomach will become more stable, and what was once a concern will become a strength. Begin practicing carbohydrate intake during training sessions, AT LEAST 4 weeks before the start of the competition season.

This approach can significantly enhance your carbohydrate oxidation, providing more energy, postponing the onset of fatigue ("hitting the wall"), and reducing the risk of digestive issues. The study we previously described utilized sports drinks or other carbohydrate-rich sources during sessions, in addition to a slight increase in daily carbohydrate intake. However, for you, the goal should be to push your individual intake ceiling. This means you should consume an amount that is close to your limit. This is done to force the body to optimize absorption and the ability to utilize carbohydrates. Similarly, sometimes you need to train above your threshold to push it higher, rather than just settling for moderate-intensity workouts.

Your body excels at what it is exposed to. If you train in a specific way and adopt a certain lifestyle, your body will adapt accordingly. If you're among those who experience discomfort from hydration and/or energy intake, our recommendation is to specifically train to overcome this weakness. By doing so, your stomach will become more stable, and what was once a concern will become a strength. Begin practicing carbohydrate intake during training sessions, AT LEAST 4 weeks before the start of the competition season.

This approach can significantly enhance your carbohydrate oxidation, providing more energy, postponing the onset of fatigue ("hitting the wall"), and reducing the risk of digestive issues. The study we previously described utilized sports drinks or other carbohydrate-rich sources during sessions, in addition to a slight increase in daily carbohydrate intake. However, for you, the goal should be to push your individual intake ceiling. This means you should consume an amount that is close to your limit. This is done to force the body to optimize absorption and the ability to utilize carbohydrates. Similarly, sometimes you need to train above your threshold to push it higher, rather than just settling for moderate-intensity workouts.