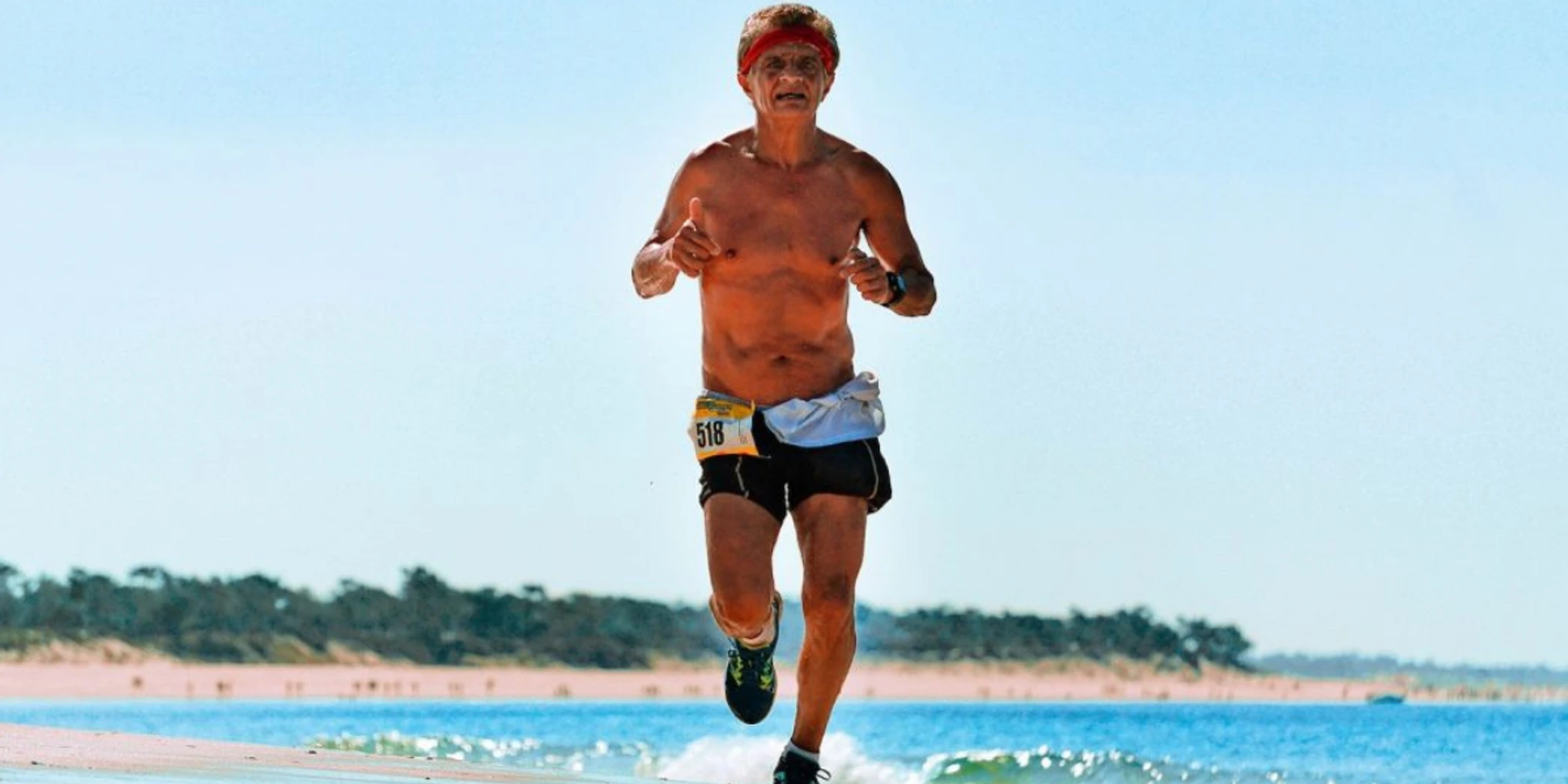

Age and athletic performance part 2 - Strong & enduring forever?

Endurance and Conditioning Training

So okay, we lose oxygen uptake as we age, but the decline is certainly not linear and, above all, the decline is less if we train than if we do not. A sedentary 60-year-old (where we statistically lose oxygen uptake the fastest) loses about 12% in oxygen uptake over a 10-year period, while the corresponding figure for those who train regularly is 5.5%.

Can older adults increase oxygen uptake and muscle mass? Is that possible?

The quick answer is yes, it is possible to increase both oxygen uptake and muscle mass. There is a cool study on this where they had 7 people aged 20 and 6 people aged 74 follow a 12-week cycling training program. All participants were relatively untrained but exercised at least 1 day/week for at least 20 minutes each time.

The training and diet were monitored and were equivalent between groups in relation to their baseline values. The older participants started at 22ml/kg/min and the younger at 40ml/kg/min in oxygen uptake. During the study, they trained 3-4 times/week for 20-45 minutes per session, and the intensity increased continuously from 60% of maximum for 20 minutes up to 80% of maximum for 45 minutes. Participants' diet and weight were monitored so they remained weight-stable during these 12 weeks. The results showed that aerobic capacity increased by 16% in younger participants and 13% in older participants. The amount of muscle mass in thigh muscles increased by 5% in younger and 6% in older participants, primarily due to an increase in type 1 fibers (endurance).

There are many similar studies that show the same results, and what does this mean in practice? Well, it means that a 70+ year old and a 20-year-old can both get the same training response relative to their baseline values. However, younger people experience more absolute increases in terms of grams of muscle mass and oxygen uptake gains in absolute terms. This is what actually correlates with performance, but it is still fun to see and perhaps break the myth that a 70-year-old cannot build muscle. Because looking at this study, 74-year-old guys are building strength percentage-wise more than 20-year-olds if they start training 😉

I have a great fitness base from my hockey playing 20 years ago...

We hear this type of statement quite often, and there are indeed correlations between those who are active as younger people and those who often remain more active as older individuals. BUT, your body will not conserve muscle cells, mitochondria, and a well-developed capillary network for 20 years if it is not needed. A basic rule is that our body does not conserve structures that are not necessary.

However, the correlation holds, and those who are physically active when they are young often continue to be so more or less throughout their lives, as training becomes a part of your lifestyle. There is potential for a high training volume and capacity in younger years to have advantages later in life, but this is not scientifically established. What is clear is that current training is the most significant determining factor for your current fitness. If you stop training from the age of 50 onward, you will soon have the same physiological profile (i.e., weight, metabolic values, health, risk of injuries, fractures, etc.) as a completely untrained 50-year-old.

The aging process has its course, and the most important lesson is to continue to train, regardless of age. So keep your training volume up throughout life, as it seems that mainly the volume of training correlates strongest with being a fit grandparent. Do shorter strength training sessions twice a week during your base training, and ideally 1 session per week during the rest of the year except during the most intensive competition periods when you can skip strength training completely in favor of sports-specific training and peaking.

Don't stop strength training

Longitudinal studies over many many years following people through their life cycle clearly show that older athletes lose muscle mass and gain more fat, despite the training volume being the same. However, there are exceptions, and one group of people does not lose muscle mass to the same extent, and that is those who maintain strength training as a complement to their conditioning training. The trend has been observed in several studies among men and women but is most pronounced in men. A study from 2006 examining how strength training affects testosterone in older and younger individuals shows that the relative increase in testosterone is equivalent in men regardless of age. However, the absolute level is lower in older individuals since baseline levels of free testosterone are lower. A workout session with 3×10 reps at 80% of 1RM across 6 exercises resulted in a percentage-wise equivalent testosterone increase regardless of age. But those who were 20 had higher baseline values than, for example, 60-year-olds, so the total amount of testosterone from the session was higher and the training response as well.

However, you will still lose muscle mass; we all do, and the greatest loss primarily comes from our type 2 muscle fibers, which are our explosive/anaerobic fibers. This is also evident in that older individuals do not need to lag so far behind younger ones in longer distances where type 1 fibers are more important. There are plenty of examples of athletes who perform very well well into their 40s and beyond.

Specific Tips for Older Runners

For runners, biomechanics play an especially important role in maintaining performance as we age. Let’s take a quick look at this area, which may not be as researched as one might think. In a study that examined the effects of aging on our movement economy and biomechanics, 110 experienced runners (54% men, 46% women) aged between 18-60 years were studied.

In summary, it was found that cadence remains stable with age, but stride length gradually decreases, and so does the power from each step. What researchers observed after all measurements and 3D analyses in the lab was a correlation between a shorter stride length and a reduced speed. But why does stride length decrease, one might wonder?

Well, one of the biggest influencing factors that seems to hinder our performance with age is something as mundane as ankle mobility. These findings confirmed earlier studies showing that our ability to generate a propulsive force through the ankle is the primary limitation. At the same time, it also appears that our ability to generate force from the hip decreases with age. No differences in force production around the knee joint have been found between older and younger individuals. Thus, it seems that our running speed declines with age, primarily due to a reduction in the hip's propulsive force, likely because it is a massive muscle that shrinks with age, while ankle mobility and the ability to transfer a propulsive force through the ankle and into the ground also decrease with age. Ankle mobility is, on average, 15-30% worse in a 60-year-old runner compared to younger 20-30-year-old runners.

Practical Applications & Tips

First and foremost – maintain ankle mobility. Don’t neglect stretching of the calves and hamstrings, and do your threshold intervals. It undeniably seems that ankle mobility is one of the primary limiting factors preventing older athletes from running as fast as younger ones.

Glute training and even more glute training seems to be awesome. Our Gluteus Maximus, or large glute muscle, is the muscle that drives us forward. So keep it well-trained and maintain performance longer. Hip lifts, deadlifts, and squats are all excellent exercises for strengthening the glutes.

Be aware that your recovery time may be a day or so longer than that of younger athletes. So focus on eating properly after each session and give your body an extra rest day if you feel it's needed. Simply listen to your body!

We all get older and will become stiffer, slower, and a bit more tired, so what? There’s nothing stopping us from continuing to train and enjoy endurance sports. So keep training both your intervals and strength training, and you’ll be able to enjoy long runs, adventures, and outpace younger participants in both the Vasaloppet and the Vätternrundan!

//Team Umara